A Guide to Collaboration with Community Partners to Address Impaired Driving on College Campuses

Developed in partnership with the Texas Department of Transportation and Texas A&M Transportation Institute

This Guide to Collaboration aims to complement theoretical frameworks and connect people on how to best serve colleges based on 11 years of experience implementing the U in the Driver Seat program.

There is an imperative need to bridge the gap and support the 18-24 age group on college campuses to reduce impaired-related traffic crashes, which remain one of the leading causes of injury and death across the nation. Car crashes are part of a much larger system - influenced by many variables that do not exist in isolation, including policies, enforcement, environment, traffic, culture, etc. Preventing impaired driving requires the need for multiple interventions by different actors across various sectors to achieve meaningful change.

The Problem

Despite significant improvements in road safety, car crashes have continued to take their toll in our country, with the highest crash death rate of all high-income countries (1). Unfortunately, the toll is often borne by our nation’s youngest and most vulnerable populations, who are often just beginning their journey into adulthood.

56566

CAR CRASHES COST ROUGHLY

SINCE 2017, CAR CRASHES HAVE KILLED OR INJURED OVER

LIVES ANNUALLY (1)

YOUNG ADULTS NATIONWIDE (2)

1.35 MILLION

6,328

Young lives lost in TX (3).

Our Vision for Change

Our vision is to educate collegiate stakeholders on principles of effective prevention and strategies that will bring about desired behavior change.

The values and beliefs shared among groups of road users and stakeholders that influence their decisions to behave or act in ways that affect traffic safety.

(Ward & Otto, 2019)

Traffic Safety Culture

When considering how to change undesirable behaviors, like impaired driving, we must look at the social environment – from the individual level to the relationship level to the community level and, ultimately, the societal level. What students think about a behavior is directly related to what they do.

Considering impaired driving through the lens of traffic safety culture can help focus on ways to grow shared belief systems that support protective behaviors and decrease risky behaviors. Traffic Safety Culture is a model coined by the Montana State University Center for Health and Safety Culture as a key factor to manage and sustain safe roadway transportation systems and comes from human and social science disciplines that are not typically included in traditional traffic safety (4).

Opportunities for Collaboration

Reducing impaired driving-related crashes is a "wicked problem", defined by Systems Theory as complex problems caused my multiple determinants (5). These problems cross different sectors such as environment, health, and education. For purposes of this guide, TTI is advising on college-level impaired driving prevention through the lens of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute's Center for Community Health and Evaluation – Collaboration Model (6).

Select an essential element to see how it's defined and a U in the Driver Seat application.

Community & Equity

Shared Purpose

UDS Application

An agreed-upon vision and mission, joint priorities, and a sense of collective ownership that centers equity and community context.

UDS has found shared purpose with college campus groups such as the campus health and wellness centers, police departments and student activities. Complete visions may not always align, but it's good to find shared interests and build upon them for mutual benefit.

Essential People

at the Table

Intentionally engaging multi-sector and diverse representation beyond those voices typically influencing health-related work. This includes community members who are affected by the group’s work.

UDS Application

Involving college students is a key component of the UDS program. Hosting the Collegiate Advisory Board each year and obtaining student and faculty/advisor feedback helps influence and evolve the work to meet the needs of the college campus. Other essential people include campus police, local and state governments, TxDOT, etc.

Adequate Structure

& Support

Dedicated staff with adequate capacity to do the work; appropriate committees, rules, and processes to achieve the goal; structures for clear decision-making and communication incorporating community voice; data/analytics capacity; and adequate resources.

UDS Application

Connecting college campuses with the many resources available across the state of Texas is vital to their success. Relationships are powerful, and one program or organization doesn’t need to do all the work. Support can be provided through consistent and clear communication.

Taking Action

A concrete action plan with identified resources and methods for measuring success that support collective progress and achieve outcomes desired by the community.

UDS Application

Every action plan may look different and one benefit of the UDS program is that it’s adaptable to any college atmosphere. While it would be great to measure success on college campuses, UDS has found getting participation and evaluation of programming from college groups difficult without administrative support and adequate in-person/on-campus time with students.

Effective Leadership

Clear leaders who foster trust and distribute power and decision-making, have credibility, effectively communicate and steer the collective work forward.

UDS Application

Effective leadership of impaired driving prevention on college campuses is a shared responsibility between program leadership, student organization leadership, and campus advisor leadership. Students have credibility with their peers, advisors have credibility with their administration, and the program does its best to fit within the needs of both.

Active Collaboration

All partners actively participate in planning and carrying out work as they operate in the shared interest of the community.

UDS Application

U in the Driver Seat has found a benefit in connecting with other impaired driving prevention activities or programs by asking for help in carrying out events or raising awareness about the problem of impaired driving around the state. Every campus community is different, especially when you begin to consider local governments and businesses, recent injuries, and campus policies.

Evidence-Informed Strategies

Toggle through to learn more about Evidence-Informed Strategies

Counterproductive Strategies for Collegiate Collaboration & Outreach

Role Play

- Role-play can sometimes be counterproductive when working with colleges for impaired driving outreach because it may come across as insincere or disconnected from the realities students face.

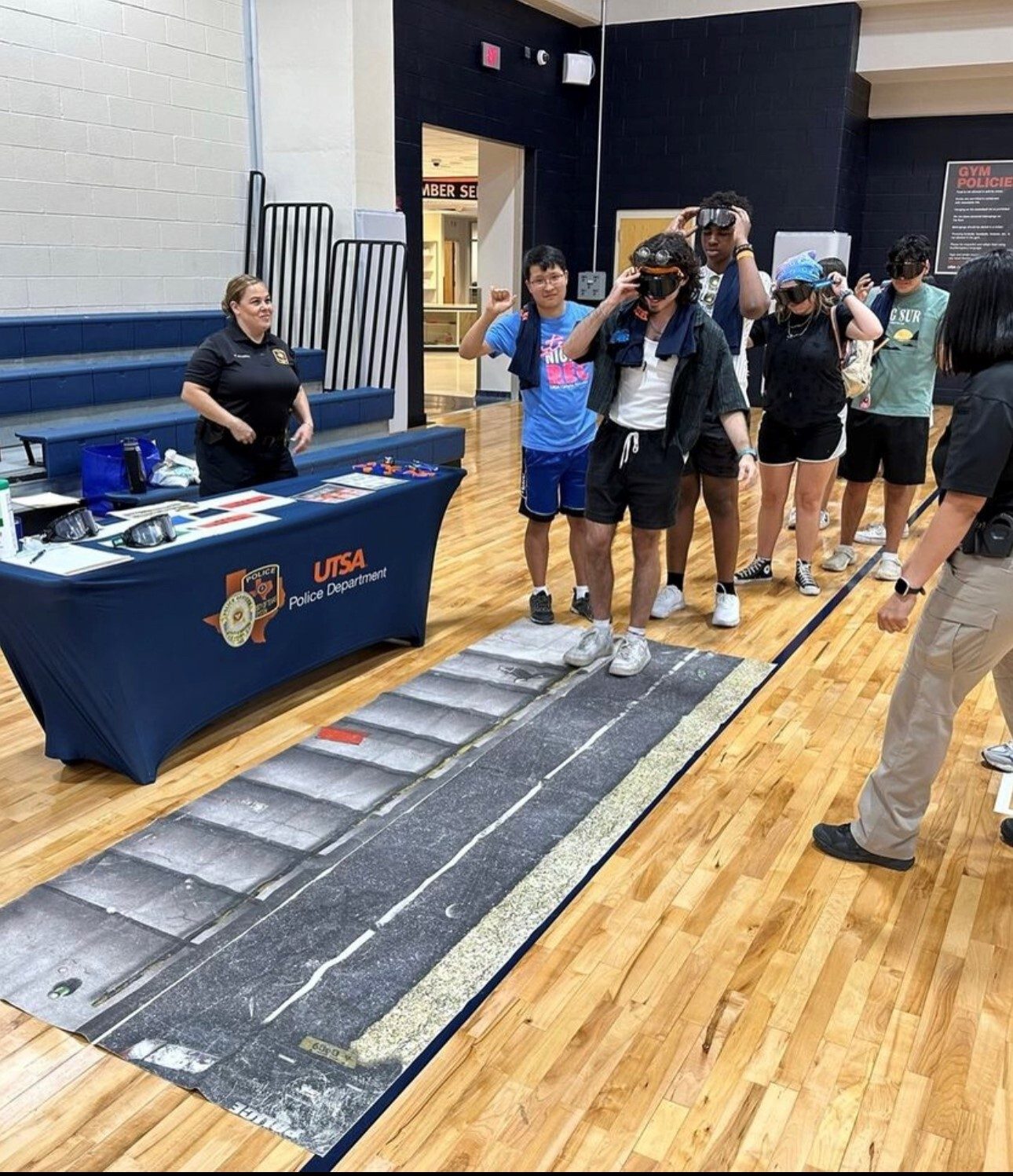

- Use of impairment props (such as goggles).

Impairment props are a catch-22. While it's a crowd-pleaser and gets the attention of students and the media, the safety message can get lost if users don't take the activity seriously. If using these props, make sure you include an educational component to the activity.

UDS Tip

Myth Busting

- Studies show people are more likely to recall myths as facts. It is common to see articles share a myth in bold font and then address it with a detailed explanation of why it is false. Unfortunately, truth gets lost in the lengthy explanation while the highlighted myth sticks.

- Illusion of Truth Effect - Commonly held beliefs and repeated statements are easier for our brains to process and therefore perceived to be more truthful than new information. Familiarity breeds belief. Sadly, myth-busing actually becomes myth-reinforcing.

When debunking a myth, lead with the fact, not the myth. Keep the fact brief and to the point so that it sticks. Then, before you mention the myth, tell people that you're about to mention a myth and explain why it is false.

UDS Tip

Personal Testimony from People in Recovery

- Can normalize drug and alcohol use and reinforce the idea that "everybody is doing it."

- Should not be used as a universal prevention method but rather as a tool for addressing targeted audiences of those in recovery.

Vet speakers before you contract with them. Ask to receive a sample of their presentation to see how flexible they may be to adapting their presentation to your specific college atmosphere.

UDS Tip

Reinforcing Exaggerated Social Norms

- Sensationalized information about high-rate use, even when true, normalizes the perception that everybody drinks or uses drugs.

- Discounts the young adults who are making healthy choices.

- As previously noted, positive community norming takes the opposite approach by highlighting those who not using drugs or drinking.

Scare Tactics

- Gruesome displays may arouse emotions but don’t impact behavior or intentions long-term; they can also serve as a trigger to those who have suffered a similar tragedy.

- For those truly at-risk, they don’t connect their current behaviors to such “future” images and may even be encouraged to rebel against the message to prove it wrong.

- Fear arousal can backfire when young adults have access to contrary information and experiences.

Positive community norming takes the opposite approach and is rooted in The Science of the Positive which is a way to grow positive behavior, like finding a designated driver or not drinking underage.

UDS Tip

Scare Tactics

Reinforcing Exaggerated Social Norms

Personal Testimony from People in Recovery

Myth Busting

Role Play

Select a strategy to learn why it's counterproductive along with a UDS best practice tip to use instead.

Model of Success

Ultimately, relationship-building and collaboration are key to creating sustainable change on your campus and in your community. When eliminating impaired driving becomes a shared responsibility by all, belief systems that promote positive behavior can be established and sustained.

For more information, questions, or consultation you may contact Gabriella Kolodzy, g-kolodzy@tti.tamu.edu, of the Texas A&M Transportation Institute Youth Transportation Safety Program.

To learn about the U in the Driver Seat program visit www.u-driver.com.

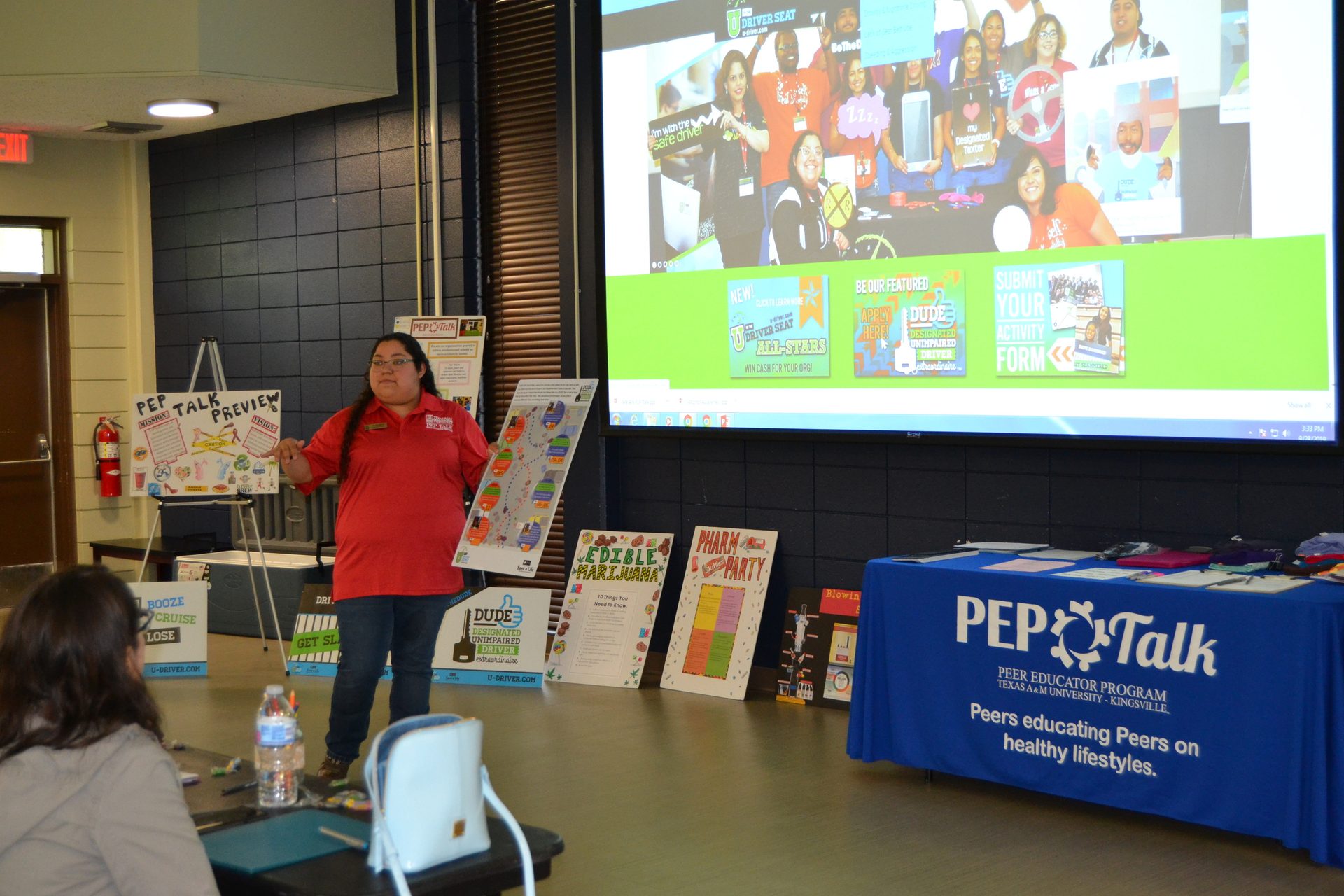

The Student Health and Wellness program at Texas A&M University - Kingsville has utilized the UDS program through their PEP Talk (Peer Educator Program).

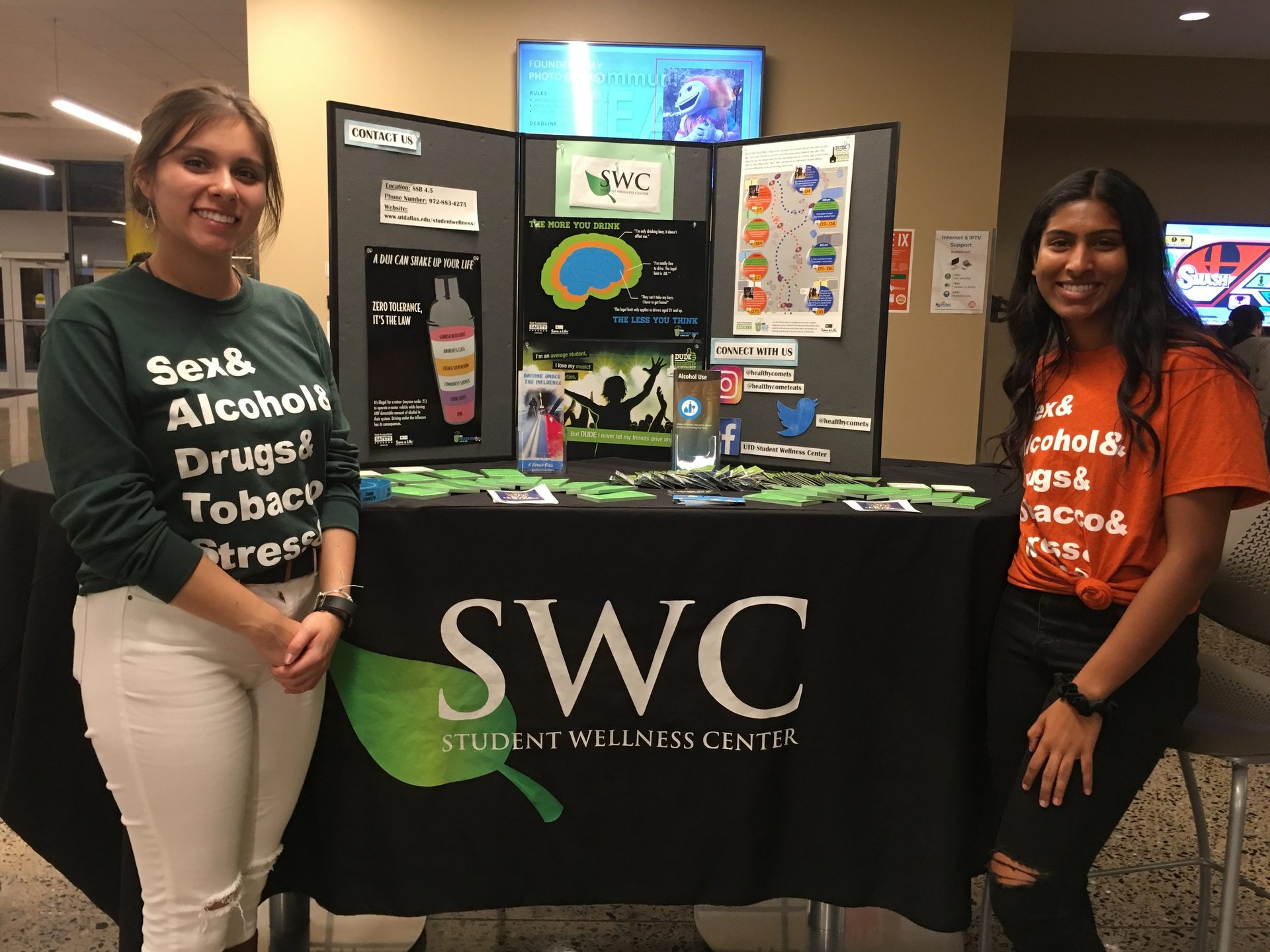

The Student Wellness Center at the University of Texas at Dallas conducts peer-to-peer impaired driving outreach in their student union.

U in the Driver Seat staff collaborate with campus police to host impaired driving outreach on college campuses like at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Where Does the Road Go From Here?

There is a need to complement theoretical frameworks and connect people on how to best serve colleges. TTI has found a few good ways to serve colleges and identified some opportunities to adapt to their needs based on 11 years of experience implementing the U in the Driver Seat program.

Colleges are an ideal place to implement impaired driving prevention education due to campus polices and existing health initiatives.

1

It will take community collaboration with a shared purpose.

2

College campuses are as unique as the lived experiences of the students that attend them. Tap into the cultural identity of each school.

3

Find commonality with campus interests, like the connection between alcohol and mental health, to connect impaired driving awareness.

4

Evaluate the effectiveness of existing or new approaches to impaired driving prevention.

5

1

2

3

4

5

Resources & References

The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated in the interest of information exchange. The report is funded, partially or entirely, by a grant from the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT). However, the TxDOT assumes no liability for the contents or use of thereof.

2. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2022. FARS persons Killed in Fatal Crashes

3. TxDOT Crash Data https://ftp.txdot.gov/pub/txdot-info/trf/crash_statistics/2022/34.pdf

4. Ward, N., Otto, J., Finley, K. (2019). Traffic Safety Culture Primer. Bozeman, MT: Center for Health and Safety Culture, Montana State University.

5. Machata K., Alexopoulou G., Susanne Kaiser S., Ward N. (2018) Traffic Safety Cultures and the Safe Systems Approach Towards a Cultural Change Research and Innovation Agenda for Road Safety. Deliverable D5.1 of the EU project TraSaCu.

6. Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, CCHE Center for Community Health and Evaluation - Collaboration Model https://cche.org/our-work/tools-and-resources/collaboration-model